Public company mergers are the most prominent, profitable contracts that M&A lawyers negotiate, but they may not be the most challenging to structure. Such agreements are only in effect between the signing and closing of a deal and therefore raise a limited number of drafting challenges. Joint ventures and other long-term contracts raise thornier issues that may not be easy to resolve, Michael Klausner and Guhan Subramanian write in their new book “Deals: The Economic Structure of Business Transactions.”

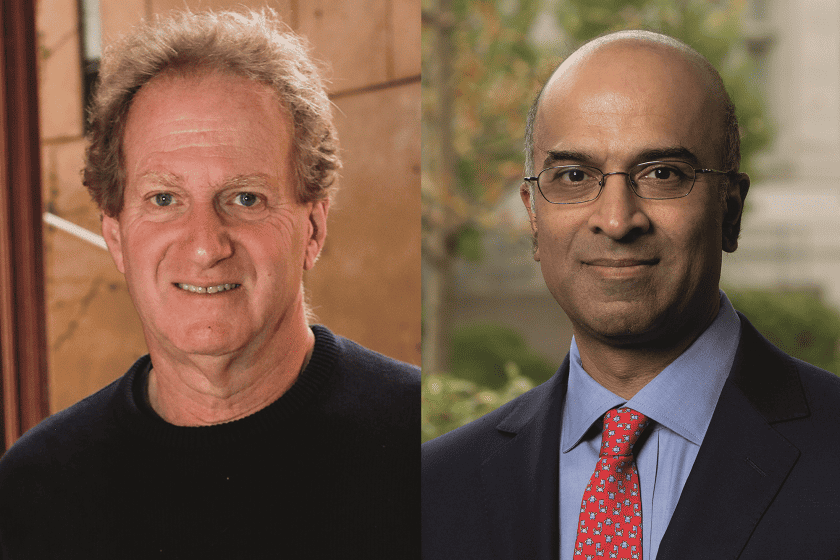

Klausner, a professor at Stanford Law School, and Subramanian, a professor at Harvard University’s law and business schools, hypothesize that there is “an underlying order to business transactions” that’s applicable to transactions well beyond mergers and acquisitions. They set out to explain some of the principals of that order in a book aimed at students and young M&A professionals, as well as others who want to better understand the conceptual underpinnings of dealmaking.

The authors consider a range of issues, including bargaining power as well as the challenges of incomplete information and verifying a counterparty’s performance. Several of the topics they take up involve long-term contracts, including asset- or relationship-specific investments and exit mechanisms. They note a number of pitfalls in drafting such arrangements, which in part reflect the impossibility of foreseeing how circumstances may change over the course of an extended commercial relationship.

Klausner and Subramanian also discuss earnouts and contingent value rights. “Writing an earnout that cannot be manipulated is difficult,” they observe, because of the gamesmanship in which the buyer may engage to avoid paying an earnout to selling shareholders after a deal closes.

That comment could also be made about CVRs.

As the authors point out, large pharmaceutical companies often include CVRs as part of the consideration in purchasing smaller biopharma companies, though the payouts on CVRs are often based on regulatory milestones that are outside of the control of the buyer.

The authors observe that much of the ambiguity in contracts is deliberate, since both parties may find it preferable to precision on a given point. In the final words of the book, Klausner and Subramanian quote a veteran talent lawyer who observes, “The last thing you wish to create is clarity that you don’t have what you wanted.”

Editor’s note: The original version of this article was published March 19, 2024, on The Deal’s premium subscription website. For access, log in to TheDeal.com or use the form below to request a free trial.