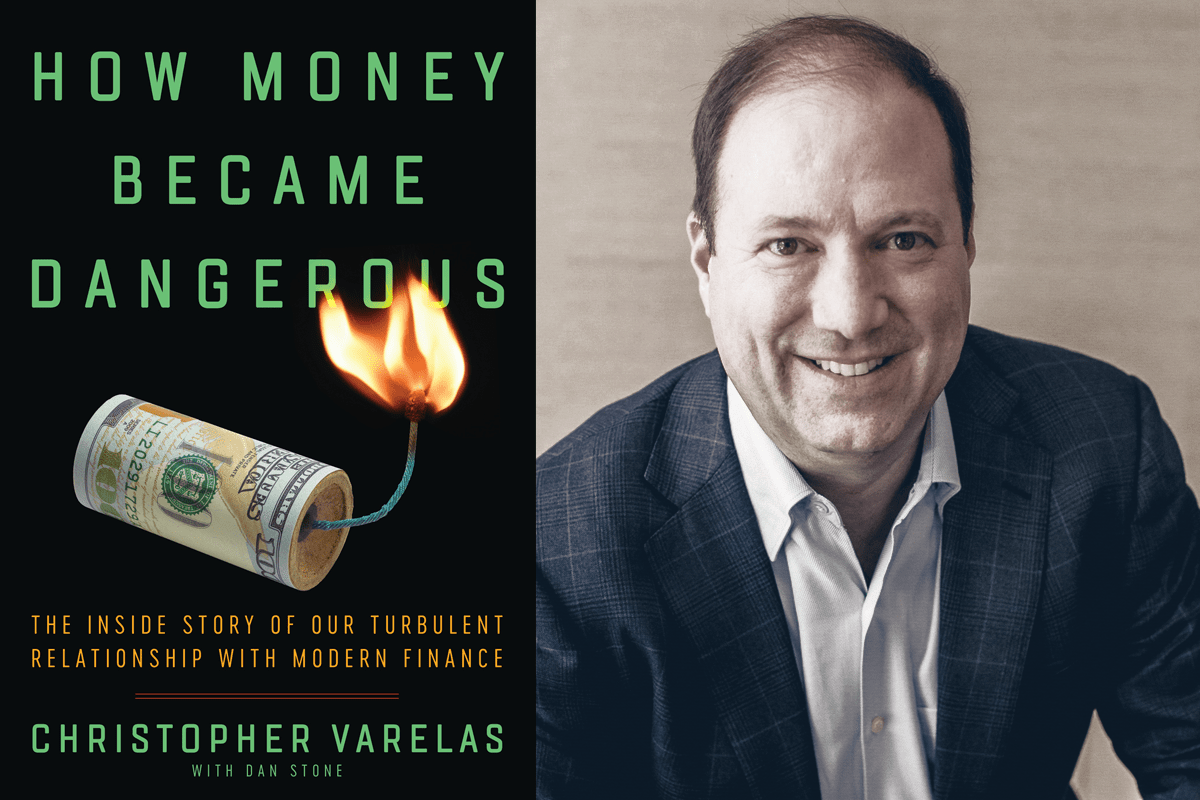

Christopher Varelas wields a similar reportorial ruthlessness in his new book, “How Money Became Dangerous: The Inside Story of Our Turbulent Relationship With Modern Finance,” which he co-wrote with Dan Stone. Varelas traces the increasing complexity of the financial world through his 20 years as an M&A banker at Salomon Brothers and Citigroup Inc. (C), where he rose to run technology, media and telecommunications investment banking before retiring in 2008 to help launch Riverwood Capital, a Menlo Park, Calif.-based private equity firm. In his time as a banker, Varelas met a host of memorable characters whom he depicts with a candor that ranges from the loving to the vicious.

As Varelas notes several times in the book, he has an atypical background for a banker, which helped him view his profession with a high level of detachment. He grew up in Orange County, Calif. and helped pay for his education at Occidental College in Los Angeles by working for four years at Disneyland, where he was immersed in Walt Disney Co.’s (DIS) obsessive approach to customer service and got his first exposure to a hostile takeover bid in 1984 when Saul Steinberg took a brief run at the company and walked away with $50 million in greenmail.

After college, Varelas spent three years in corporate banking at Bank of America Corp. (BAC) in Los Angeles. Among the accounts he covered were Los Angeles diamond and gold merchants. There was Barry Kagasoff, a man of unimpeachable honesty and irrepressible crudeness. When one customer says that he wants diamonds of F-level clarity for his wife’s earrings rather than the cheaper G diamonds, Kagasoff sets him straight: “Listen to me. If anyone gets close enough to your wife’s ear to know whether they’re G or F color, you should take a crowbar to his fucking head.” Barry’s judgment of other merchants’ creditworthiness was better than any financial analysis in a notoriously secretive industry.

Then there was Nazareth Andonian, a gold wholesaler whose business increased considerably just after Varelas started covering him. Nazareth flashed his money on cars and prostitutes as his daily deposits topped $1 million. It turned out that he was laundering money for Pablo Escobar’s Medellin drug cartel, an indelible lesson for Varelas in the importance of assessing character, which he had done a poor job of in Andonian’s case. Convicted on federal charges, Nazareth and his brother Vahe are both still in prison.

Varelas heads to Philadelphia to attend the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and ends up on the trading floor at Salomon Brothers in the summer of 1989, the year Michael Lewis published his classic book, “Liar’s Poker.” Varelas has sales ability but finds the trading floor uncongenial and instead lands a job as an associate in Salomon’s investment banking division. He’s an improbable banker. Eduardo Mestre, then the head of the unit, told Varelas that he seemed like someone who “would just sit there taking up space.”

But Michael Carr, who “looked like a magazine ad for Wall Street—impeccably dressed, hair always in place, megawatt smile, seemingly born in a suit and tie,” as Varelas puts it, evaluated him differently. “You don’t have to try to create a separate persona,” Carr, now the co-head of global M&A at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. (GS), told Varelas. “Your thing seems to work.”

Varelas was able to bond with people like Dick Heckmann, who built U.S. Filter through a series of acquisitions and then sold the supplier of industrial water treatment and services to Vivendi SA’s Jean-Marie Messier in 1999. Heckmann clinches the deal by ordering a bottle of Opus One wine at a dinner with Messier and uncorking a classic line. The wine, Heckmann tells the Frenchman Messier, “is the collaboration of your greatest winery and ours, Rothschild and Opus One. They came together to make a great bottle of wine, and I think we should come together to make a great bottle of water.”

The two men sign the merger agreement, and Heckmann is on his second appletini 15 minutes after the Varelas and the US Filter team have boarded the corporate jet for the flight from Paris back to the U.S. “Six billion dollars in an all-cash deal,” Heckmann enthuses. “Are you kidding me? We’ll be shitting French francs out the exhaust pipe the whole way home.” Indeed, the deal turned out very badly for Vivendi and was a career-killer for Messier.

In 1998, Salomon was absorbed into Citigroup, and Varelas crosses paths with Citi CEO Sandy Weill, who comes off as a bloviating buffoon. Before one 2000 meeting, Weill boasts that he might buy Bank One just to spite Jamie Dimon, whom Weill had recently fired for refusing to promote Weill’s daughter Jessica Bibliowicz. Dimon had called Weill that weekend to say he’d been offered the CEO spot at Bank One and make sure Weill wasn’t planning on buying the Chicago bank. (Weill didn’t buy Bank One, which ended up merging with JPMorgan Chase & Co. [JPM] in 2004.) Weill then went on to brag about getting analyst Jack Grubman to change his recommendation on AT&T Inc. (T) and thus win a role on AT&T’s upcoming IPO of its wireless unit.

In a casual conversation, Varelas writes, “The CEO of the most powerful bank on the planet had just told us two stories that confirmed our suspicions that he was a man of questionable character, and he had told us these stories as nonchalantly as if he were describing a golf match or a weekend barbecue.”

Varelas hated working at a financial supermarket, and he especially hated Bonus Day, “a steady downpour of bitterness” as bankers granted millions of dollars complain that they had been underpaid. “Ungrateful bastards,” Varelas thinks as he leaves the office after 16 hours of telling underlings how much they were to be paid. Fittingly, for a profession that “obliterated your ability to maintain healthy relationships outside of the office,” as Varelas puts it, Bonus Day is the most important one of the year.

Varelas doesn’t say much about his time at Riverwood, though he does describe a trip to Coachella with Michael Tedesco, a former Salomon colleague, to attend a party thrown by The Influential Network, a company in which the two had invested. As they’re waiting for their private jet to leave, Varelas writes, “A kid with a flowing mane of blond hair shot across the tarmac on a skateboard, wearing loud floral patterned shorts and a matching tank top,” skidded to a stop, and yelled, “We’re flyin’ PJ!” Logan Paul earned his seat on the plane by being an influencer with 59 million followers on social media, a reach that earned him $14.5 million in advertising revenue between June 2017 and June 2018.

At the several-day-long party The Influential Network throws at Coachella, Varelas sees not just Justin Bieber himself, but a Bieber impersonator and several others who “had simply made themselves so completely in the image of Bieber that they were unofficial doppelgӓngers.” Varelas clearly hasn’t lost his eye for the absurd. Perhaps after he’s left the world of technology investing, he’ll subject it to the same treatment he gives banking in “How Money Became Dangerous.”

Editor’s note: The original version of this article was earlier published on The Deal’s premium subscription website.